This is the second of a three-part series covering devastating strikes of the 1890s, strikes that surely helped cement anti-unionism in Donora’s founder, William Donner.

George Pullman, a railroad engineer, designed and built the first luxury sleeper cars in the country, with stacked sleeping berths that made nighttime travel comfortable and reasonably priced. Pullman cars became hugely popular and in the middle 1900s were often featured in films, such as Hedda Hopper’s 1931 thriller The Mystery Train and Billy Wilder’s 1959 hit comedy Some Like It Hot.

Pullman built an eponymous company town to house workers for his factory and required all workers to live there. Housing costs in the town were as much twenty-five percent higher than in the surrounding areas, and when Pullman began cutting wages in late 1893 a conflict between management and labor seemed unavoidable.

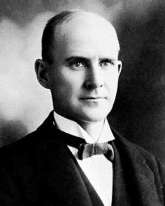

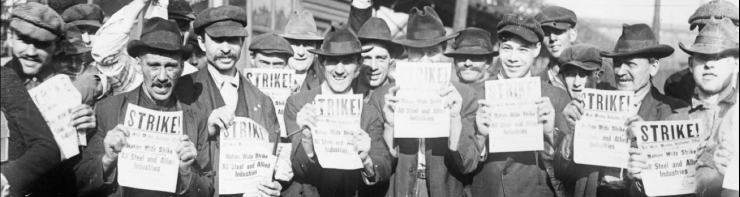

By the spring of 1894 Pullman had cut wages by twenty-five percent. Workers revolted. Thousands walked off the job on May 11, closing the entire plant. Through coincidence, and perhaps fate, a new union had recently formed and was meeting in nearby Chicago. The union, the American Railway Union (ARU), was spearheaded by Eugene Victor Debs, a rising leader in the labor movement.

Debs wanted Pullman workers to join the ARU, but they refused. So Debs, whose union members included switchmen, told his Chicago switchmen that they could no longer manage Pullman cars in railroad yards, at which point the switchmen were, predictably, fired.

Debs figured that a switchman strike would encourage railroad workers elsewhere to join ARU and also strike. He was right. By June 30 about 125,000 rail workers on twenty-nine railroads had walked off the job rather than work with Pullman cars. The coordinated strikes crippled Chicago rail yards and blocked nearly all rail transport through the city, one of the nation’s most important rail centers.

Desperate to appease the unions and dampen tensions in the city, President Grover Cleveland quickly signed S. 730 into law, a bill that had been languishing in the Senate for a year. The bill proclaimed that

the first Monday of September in each year, being the day celebrated and known as Labor’s Holiday, is hereby made a legal public holiday, to all intents and purposes, in the same manner as Christmas, the first day of January, the twenty-second day of February, the thirtieth day of May, and the fourth day of July are now by law made public holidays.

Thirty states had already been celebrating Labor Day, so Cleveland’s signature was viewed largely as a political move. “It was a way of being supportive of labor,” explained Indiana State University historian Richard Schneirov. “Labor unions were a constituency of the Democratic Party at the time, and it didn’t look good for Cleveland, who was a Democrat, to be putting down the strike.”

Cleveland wanted Illinois Gov. John P. Altgeld to use force to end the strike, and when Altgeld refused, Cleveland intervened. He used provisions in the Sherman Antitrust Act, as well as the Interstate Commerce Act, to procure a court injunction that blocked union leaders from “compelling or inducing” workers “to refuse or fail to perform any of their duties.”

Then he sent federal troops to Chicago in early July. That uninvited interference by the Government enraged the workers, and they began rioting. They flipped railroad cars and built blockades to prevent soldiers from entering the rail yards. “There was a lot of sympathy from people,” said Schneirov. “They would come out and try to help the railroad workers stop the trains. They might even [have been] initiators, standing in front of the tracks and chucking pieces of coal and rocks and pieces of wood. Then there would be lots of kids, lots of teenagers, out of work or just hanging around and looking to join in for the fun.”

A series of fires on July 7, 1894, presumably started by striking workers, destroyed seven buildings at the World’s Columbian Exposition, an event celebrating Columbus’s arrival in the New World. About 700 railcars were burned and some $340,000 of damage caused to the rail yards. That same day, troops from the National Guard fired into a crush of strikers, killing thirty and wounding at least twenty.

Debs and other ARU leaders were arrested, and the strike faltered. By August 2 the Pullman plant had reopened and trains again rumbled through Chicago. Putting down the strike had required a force of more than 14,000 federal troops and an assemblage of national guard troops, marshals, sheriffs, and police officers. Rail companies lost nearly $5 million in revenue, and workers lost nearly $1.4 million in wages. Debs and other ARU leaders were convicted of contempt charges and sentenced to prison. The Court stated in its decision that under the Sherman Act, “any restraint or trade or commerce, if to be accomplished by conspiracy, is unlawful.”

Debs would later form the International Workers of the World union, whose members were commonly called “Wobblies.” He also joined the Socialist Party and ran several unsuccessful campaigns for president. He was arrested in 1918 for giving an “anti-war speech” in Ohio.

Leave a Reply