Donora’s heroic physicians during the smog of 1948 learned their trade long after medical education had recovered from the destructive effects of the so-called “Doctor’s Riot of 1788.” The event was a bloody post-revolutionary protest against medical students in New York City stealing corpses to study anatomy. The incident ravaged the public’s perception of medical education, a perception that took decades to turn around.

At the time of the riot the Revolutionary War had been over for five years, and the nation was in chaos. Congress was stone-broke, and each state was carrying overwhelming debt. War veterans, even after demobilizing, weren’t being paid. Laws were haphazard. Mob control remained in the purview of each state’s militia. And the great George Washington wouldn’t be inaugurated as the nation’s first president for another year.

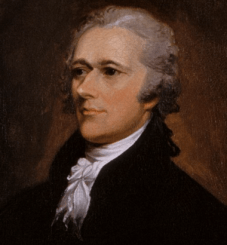

Alexander Hamilton was by that time an American hero, but when he was attending King’s College (now part of Columbia University) before the war he studied anatomy with Samuel Clossy, first professor of anatomy at the school and one of the first anatomy professors in the country. Clossy, born in Ireland, brought with him to America many of the practices common there, including the robbing of graves to satisfy his need to teach anatomy, which medical students then and now must master before they can practice medicine.

Michael Sappol, in his book, A Traffic of Dead Bodies, writes about Clossy’s first anatomy class at King’s College:

His first subject was a 20-year-old white woman (probably stolen from a church burial ground) and then “a female black” who bore a “beautifull carving on the Neck breast and belly…. Hieroglyphics possibly of the kingdom of Angola.” But for the third part of the lecture series, he was unable to obtain a body: he and his confederates were so well known “that we could not venture to meddle with a white subject, and a black or Mulatto I could not procure.” Unable to complete the curriculum, the course ended after 44 evenings.

Medical students were still digging up bodies long after Clossy and Hamilton had both left King’s College. Mostly they used corpses from a nearby potter’s field and from the “Negroes Burying Ground,” a short walk north on Broadway.

In April 1788, according to one prominent rumor, a medical student named John Hicks is said to have shown a youngster out a window the severed arm of a woman. Hicks told the boy it was his recently-deceased mother. The boy ran home and told his father, who immediately visited his wife’s grave only to find her body missing.

Hicks had no idea at the time that his childish behavior would lead to a riot and as many as twenty deaths.

Stay tuned for Part 2…

Leave a Reply to When the Publick Rose Up Against Its Doctors, Part 2Cancel reply